The church stands prominently at the centre of Whiteparish village and we owe the overall visual impact of the building very much to the 1870 restoration by William Butterfield. There are good photographs, paintings and drawings of the building before restoration to show us how it had looked before that date and even a pair of before and after photographs taken from the same spot. The earliest historical records confirming the existence of the church date from 1278, 1291 and 1297, but the Listed Building Status describes the building as 12th century (and therefore Norman) and the Royal Commission book [see References] as about 1200, but reusing some pieces of sculptured stone from a building from earlier in the 12th century. This implies an earlier stone building put up at some time during the early to mid-century 1100-1200 that was taken down and rebuilt around 1200. The chancel is often described as being possibly as early as Saxon in date, but late Saxon and early Norman churches are so similar that architecture alone is insufficient to give any clear indication and I've been unable to locate any archaeological investigation of the building.

Whiteparish Church

There are short histories of the church available in many places, including Matcham's 1844 book on Frustfield, church visitor leaflets, Wikipedia, the Wiltshire Records Office website, the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England, the Listed Building Status, the Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain and Ireland and more. Full details of these references with direct web links can be found in the References section at the foot of this page, with the full text at Church Sources not available to the general public online for copyright reasons. While some of these accounts have constrained themselves to documented facts, others contain statements that I've been unable to confirm or in some cases that are either demonstratively incorrect or purely speculative.

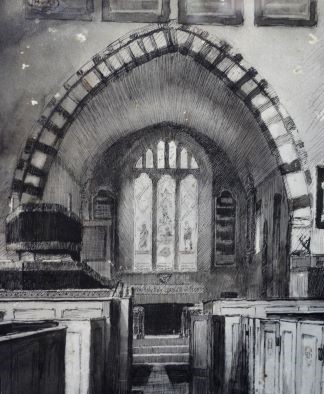

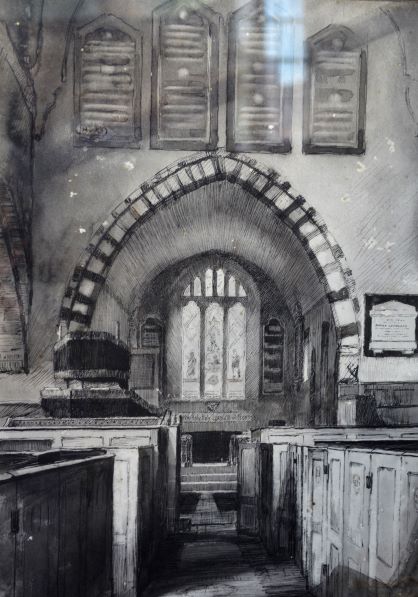

The inside of the church viewed from the west window

This would have been the view from the west gallery until it was demolished in 1870

What you will find on this page is an attempt to be impartial coupled with a desire to get to the bottom of what is fact and what isn't. To be fair, I've added some speculation of my own too. I've collected significant sections of text from these and other sources and then tried to explain what I have found to be the most persuasive account based on that and detail I've been able to collect from original sources. Unfortunately some of the source material is still in copyright, and there I can do no more than provide links and references as appropriate. Where material is out of copyright all the source text is available elsewhere on this website, although as stated elsewhere my priorities in uploading pages to the web won't always have reached pages you may be interested in seeing. If you are local and able to contact me you are welcome to urge me to make such pages of special interest to you available more quickly.

Contents of this page

- Introduction

- History of the church

- Building materials

- The early church Reused sculpted stones were from an earlier building; was the chancel originally the church?

- 12th century Nave, chancel and aisles probably built no later than 1200

- 13th century

- 14th century Single arch replaced at the west end of the south aisle arcade, with octagonal pillars

- 15th century Chancel remodelled, new east window

- 16th century

- 17th century South aisle rebuilt or recased and new windows with stone frames

- 18th century North aisle rebuilt and new windows with wooden frames

- 19th century Butterfield restoration - aisles demolished and rebuilt to a wider plan and lower roofs as seen today, font and pulpit

- 20th century Octagonal vestry added in 1969 followed by a toilet in 2000

- Monuments and paintings

- Selected features of the church

- The chancel

- The chancel arch

- The west gallery removed in 1870

- The bells and clocks in the tower

- The 1870 Butterfield restoration

- The north and south aisle arcades

- The north and south aisles

- The charity boards in the porch

- Rectors and Vicars

- The outside of the church before and after restoration

- Inside the church before and after the 1870 restoration

- Memorials

- The Graveyard

- The churchyard wall

- References

- Acknowledgements

Introduction

Having a picturesque church so well placed in the centre of the village is enjoyed by many, but quite how it came to be there is something of a mystery. There are seven entries in the Domesday Book of 1086 for what was to become the Hundred of Frustfield and ecclesiatical parish of Whiteparish, five listed as holdings in Frustfield and two as holdings in Cowesfield. At that time the two main manors in what was or became the Hundred of Frustfield were Whelpley and Abbotstone, Whelpley having a sizeable mediaeval settlement of its own around where Whelpley Farm still stands. Alderstone was tiny by comparison and centred around the triangular green bounded now by The Green, but became the centre of a new village that completely absorbed the populations of several manors.

Much earlier in time the boundaries of the manors of Whelpley and Blaxwell had met to the south and prevented the further growth of Alderstone southwards, so that the church and surgery stand close to the most southerly point of the main manor area, with Whelpley to the west and Blaxwell manor to the east meeting across the common grazing strip near the school (see this map of 1842, on which north is to the left). Instead Alderstone expanded into an area in the very southeast corner of the parish beyond the Cowesfield manors and detached from the rest of the manor, and in a strip eastwards from the top of Dean Hill. As a result it was possible for the inhabitants of Whelpley and Blaxwell to live within their own manors but very close to the church, and this is what seems to have happened. In due course the lords of Alderstone and Whelpley manors also moved to the village into what was later rebuilt as Abbotstone House (Whelpley) and a 1562 house where the surgery and Steeple Barn now stand (Alderstone St Barbe Manor House). Perhaps not coincidentally, the chapels at Abbotstone and Whelpley had been seized in the king's name and closed down in 1547.

The very name Whiteparish brings interesting questions of its own. Alderstone, Frustfield (Abbotstone and Whelpley) and Cowesfield were all in Frustfield Hundred, which essentially consisted of all of the present parish plus an outlying area to the south of Earldoms that ran westwards from Wicketts Green Farm on the A36 south of the Common Road junction. The inclusion of the word "parish" in the name shows clearly that by this date the tithings of Abbotstone, Whelpley, Alderstone and Cowesfield had all been incorporated into one ecclesiastical parish and that the chapels of Abbotstone, Whelpley and Cowesfield were chapels of ease. This is reflected in the appointment of clergy from our earliest records - clearly recorded as rectors and vicars at Whiteparish but chaplains at the three chapels. In a wider context, the system of ecclesiastical parishes had started to appear in around 900 and had been extended to most of the country by the end of the twelfth century, and presumably this ecclesiastical process had selected Alderstone tithing to have the parish church. By then the ecclesiastical parish was used instead of the manor for taxation purposes [see for instance A History of the English Parish, N.J.G. Pounds, Cambridge University Press, 2004 (I have a local copy)].

There is no mention of chapels or churches in the 1086 Domesday Book entries for Alderstone, Frustfield or Cowesfield. Whiteparish church gets its first direct mention in 1291-2 in the Taxatio Ecclesiastica, the taxation ordered by Pope Nicholas that valued all the English, Welsh and Irish churches. Use of the name Whitechurch a few years earlier in 1278 shows that the church already existed by then, and the Royal Commission book on the churches of South-East Wiltshire suggests that the whole building may have been erected around 1200. It also points out that some of the stone used, including some of the capitals at the top of the nave pillars came from an earlier building.

Map showing chapels in the Hundred of Frustfield

As already mentioned, the three other chapels in the Parish/Hundred were in the Tithings of Abbotstone (the chapel was at Moor), Whelpley and Cowesfield and are all first mentioned shortly after 1300. The various source documents give us an earliest recorded date for each building, but again don't give any clue as to how long they might have been there by that date. Whelpley and Moor chapels went out of use when they were seized in the King's name in 1547 and we don't now even know exactly where the Cowesfield and Moor chapels stood. Whelpley chapel was still intact and acting as a hen house when I was given the opportunity to go inside it between 1983 and 1993, but was already being badly broken up by ivy penetrating the walls. I was privileged to visit it again and take some photographs in 2020. The roof has fallen, but the walls still stand. The last chaplains of whom we have a record were appointed in 1464 to Cowesfield Louveras chapel, in 1538 to St Leonard Whelpley and in 1436 to St James Moor, but as mentioned above St James and St Leonard were still there to be seized in the king's name in 1547. Where Abbotstone and Whelpley chapels each served a single manor, the chapel at Cowesfield served first two and later three manors. It is interesting to note that the presentation of chaplains seems to have rotated in turn round the three lords of the manors, the chapel being described at different dates as Cowesfield Esturmy chapel, Cowesfield Spilman chapel and Cowesfield Louveras chapel, all the same building (see the list of chaplains is shown here, for instance: Cowesfield Louveras Chapel).

The plan below shows the basic structure of the church in the two key periods of its existence, neglecting for these purposes the possibility of the chancel being older. In the first stage (orange), the chancel and nave with both aisles stood from around 1200 until restoration by William Butterfield in 1870. As the blue part of the plan shows, he completely rebuilt the outer aisle walls, widening the aisles (but sparing the east and west walls of the nave). Apart from the 1969 addition of the octagonal vestry and its more recent toilet extension the chancel and nave of around 1200 and the Butterfield aisles of 1870 are still what we see today. To maintain clarity, this outline of the church's history omits lots of changes small and large over the intervening centuries: all of these are described in detail below.

Plan of church (developed from the plan in the Royal Commission book)

Showing the c1200 building in the context of the 1870 Butterfield and modern extensions (c1200 north and south aisles approximate)

As already observed, the church itself offers some tantalising clues to help in dating episodes in its history, but little reliable evidence. The chancel has often been stated to have been late Saxon or early Norman in date and to have been the original church. Other sources simply state the 1291 date as the time when the nave was added to the earlier church or even as the date of the entire building, but there is nothing to suggest that the building was in any sense new at that date and of course it must already have been there by the time the 1278 place name of Whitechurch was recorded. The Royal Commission suggests the whole building was erected around 1200, with Romanesque sculpture included from an earlier 12th century building, and this is the tentative dating I have used here.

The chancel from the north

The chancel certainly bears the scars of earlier phases of building, especially in the filled in arches on the north side, which suggest that there was at some date an aisle or vestry on the north side. If the chancel was an earlier church in its own right, then from my experience of early churches I would wonder whether there might be the remains of the foundations of a smaller earlier chancel in the churchyard immediately east of it, but only an archaeological survey would be able to uncover such a feature. Certainly the chancel is the right sort of size to be an earlier church. A further clue comes from the slight misalignment of the nave and chancel, very clearly visible from the east alongside the church wall in the Memorial Ground. Aligning church and chancel is straightforward if all the footings are laid out at once, but in extending an existing building it is extremly hard to get a perfect alignment. This misalignment does strongly suggest that the nave was added to an existing structure. While the visitor leaflets in many churches will tell you that the chancel was misaligned deliberately, this simpler practical reason seems to me to be much more likely to be the cause.

The remains in the north chancel wall of two arches and what has been described as a rectangular panel but is more probably a later window or squint.

There were frequent improvements and repairs of the structure of the building over the centuries, and the section below on the history of the church lists these in chronological order with some illustrations. Below that is a more detailed analysis of each of a variety of features within the church and an account of the substantial renovation carried out by William Butterfield in 1870.

Summary of dates

- Saxon or early Norman chancel predating the rest of the church - there is no evidence to support or refute this possibility

- 12th century: possible earlier church incorporating the Romanesque sculpture

- c1200 likely construction of church in its present form, incorporating the earlier Romanesque sculpture

- 1278 the village was listed as Whitechurch

- 1291 listed as Album Monasterium in the taxation of Pope Nicholas IV - this is simply the Latin equivalent of White Church

- 1297 listed as Album Monasterium when Andrea de Chartres was instituted as vicar under the then rector Petrus de Aulton

- 1319 the name had changed to Whiteparish

- 1324 the latest mention of Alderstone church I've spotted; after that it was always referred to as Whiteparish church

The History of Whiteparish Church

I've done my best to place each feature in the right century below, but different authorities often date the same feature differently. Where this occurs I've had to compromise and select one of the options.

Building materials

The church features a range of building materials. I've followed earlier writers in describing the dark ironstone as "heathstone" and the pillars as "greensand". There is also a pale stone that has been described as Chilmark stone. The older parts of the building in the chancel and the east and west walls of the nave are principally of flint, clearly a local material from the chalk within the parish, interspersed with occasional dark and light stones, at least four of which are reused sculpture in the west wall. There are a few bricks and even one or two tiles within the structure, notably in the base of the northeast corner of the north wall of the chancel. Corners and arches are constructed from heathstone in what appears to be the most altered section of the chancel on the north wall, and it is probable that many of the randomly placed dark stones in the north chancel wall came from the parts of these features that have since been rebuilt.

DSC_0490.jpg)

Stone patterns: SE corner of chancel alternate colours, NE corner of chancel dark stone, E side of chancel arch alternate with dark above all round, W side of chancel arch alternate with (mostly matching) alternate above, Butterfield east window of south aisle alternate

The northwest corner of the chancel features alternate light and dark stones as found in the chancel arch, although whether these are of the same or different dates is not clear. Interestingly the large stones of the chancel arch are lined above with dark stones on the east side like the north chancel wall features, but the west (nave) side has these small stones in alternating dark and light to match the arch itself. The south wall of the chancel appears the least sound, with a corner buttress and irregular surface, but it is all rendered, making it more difficult to reach any conclusions on age from the outside. All the parts of the church reconstructed by Butterfield in 1870 feature a characteristic chequered pattern of light and dark stone interspersed with flint panels. Finally there are mentions in some references to chalk used within the structure and of some brick sections of wall: there's a section of brickwork on top of the west wall inside the tower, for instance, covered by shingles on the outside.

Butterfield's 'trademark' stonework in the restored parts of the church

featuring heathstone, Chilmark stone and flint, all of which are found informally placed round the rest of the building

The roofs are all tiled with the exception of the tower, which is roofed and faced with wooden shingles. These were most recently replaced around the year 2000 [replace with exact date].

The tower, faced and roofed with wooden shingles

The Early church

There is no firm evidence of a church earlier than about 1200 except for five of the nave arcade capitals and fragments of Romanesque carved stone re-used as building blocks in the wall of the west front [Royal Commission]. These are described more fully below. The earliest documentary mention of the church is in the Taxatio of Pope Nicholas IV in 1291, but Whiteparish was already called Whitechurch by 1278, so the church was clearly already there by that date. Alderstone, the manor whose church this originally was, is first mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 as a one hide manor held by Aldred both before and after the Norman Conquest, but no church is referred to in that entry. Records of rectors and vicars are no more helpful in establishing an early date, the earliest listed rector Robertus de Chartres being replaced in 1297 by Petrus de Aulton.

In a wider sense we know that our area was Christian in Roman times, but that from the arrival of the Saxons in this area in the years immediately following 495 paganism ruled until Birinus arrived in Wessex in 634. Birinus baptised king Cynegils of Wessex in the following year, 635, and presumably the rest of the kingdom duly followed suit. Birinus had his See at Dorchester-on-Thames initially but this was in unstable Mercian border territory and the See was moved to Winchester in the 660s, Winchester cathedral (the Old Minster) having been founded in 642. Given the large scale of the Old Minster, Christianity had come a long way in eight years.

In 705 the Winchester diocese was divided into Winchester (covering Wessex east of Selwood Forest - that is, Hampshire and Surrey, as well as Sussex until 709), and Sherborn (Wiltshire, Dorset, Somerset, Devon and Cornwall, the last four still being in British hands at that time with their own bishops and having remained Christian from Roman times). In 909 more major changes took place. Hampshire and Surrey remained under Winchester and a new diocese of Ramsbury took Wiltshire and Berkshire. A decree of 1075 from a Council held in London required bishoprics to be removed from small towns and villages to larger towns and cities, so with some further changes to boundaries Sarum became the centre for Wiltshire, Berkshire and Dorset. The "new" cathedral at what we now call Old Sarum was established in 1092, remaining until it was dissolved in 1226 and the cathedral moved to the present building at New Sarum (now Salisbury), itself constructed between 1220 and 1258. For a comprehensive account of the early history of the church in Wessex, see History of the church in Wessex. There is also a page covering source material on Wessex. This also elaborates on the 1871 book "The Early Annals of the Episcopate in Wiltshire and Dorset" by the Rev.William Henry James, summarised here and with detailed notes on Chapter 1 The See of Wessex AD 634-705 [there is a full reference to the book and where you can consult it on that page].

The earliest churches and especially the Saxon Minsters were built from these early times, but open air preaching was common at least until late in the Saxon period. Our present church may well have replaced a wooden building dating from late Saxon or early Norman times, but here we can do no more than speculate, as there is no archaeological evidence to be had (yet).

The stones in Whiteparish church that are considered to have been reused from a church earlier than the c1200 date of the present building include five of the six pillar capitals in the nave arcades and a selection of reset 12th century stones in the west wall. The stones visible include a chevron voussoir, two apparently related voussoirs probably from the same arch and one of which may have been the head stone of the arch, a smaller piece of worked stone, and a mediaeval cresset or oil lamp. The Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain and Ireland lists the chevron voussoir, the two eastern capitals in the south aisle pillars and the three eastern capitals in the north aisle as 12th century, but the other two voussoirs are undoubtedly of similar age, bearing a similar and slightly larger beaded decoration [crsbi].

DSC_0431.jpg)

DSC_0539 small.jpg)

Romanesque sculpture in the west wall

left to right: Chevron voussoir, cresset (oil lamp), keystone of arch, another stone from the same arch and a further more worn piece

Where these stones originated is not known, but some have postulated that the chancel could represent a smaller church erected earlier in the 12th century. In that case the stones could have been available from demolished doorways in that structure, for instance a west door removed when the chancel arch was built and maybe the blocked north chancel door. The rest of the building is dated to about 1200, when stones from the chancel west wall would have been available at the right time to be incorporated in the new nave west wall. However, this timeline wouldn't account for the presence of early capitals on top of the later nave pillars, so it would seem that possibly the nave and aisles had been constructed earlier in the century and for some reason demolished and rebuilt.

The north wall of the chancel with an arch right and part of an arch left

together with a later filled in window (sometimes described as a north door)

One or more of the church leaflets suggests that the chancel arch, which is of varied Heath Stone, would seem to have been originally of the round headed Norman style, although I've found no authoritative references to this idea.

So who might have paid for the building of so substantial a church around 1200? The church is in Alderstone Manor, so we should perhaps be looking for someone associated in some way with that manor, possibly even someone returned from the second crusade (1147-1149) with new found wealth. One of the church leaflets suggests Walter Waleran, possibly also known as Walchiri, but the Walerans were hereditary wardens of the New Forest and associated with Melchet. Melchet never has had a church and its parishioners worshipped at Landford Wood church [add link], so it seems improbable that he was responsible for building one in Alderstone, especially as all three Cowesfield manors lay between Melchet and Alderstone - Cowesfield had its own chapel too. [Check that it was Landford Wood church - there is a recorded dispute over tithes or pew rents not paid by Melchet inhabitants]. In the Domesday Book of 1086 Alderstone is listed in the land of Odo and other Thanes of the King as owned by Aldred, but we have no idea who he was or who might have inherited it from him by 1200. The research goes on and for the time being this chapter of the church's history must remain obscure.

[Collecting further material here: as well as a few isolated holdings across Wiltshire, Waleran the Hunter has a complete chapter (Ch. 37) in Domesday Book with 16 separate entries. Locally he was tenant in chief (holding land directly from the king) at ... using OpenDomesday... these include land in Grimstead (tenant in chief), Whaddon (2 entries), Alderbury (tenant in chief) and West Dean. Research his Hampshire entries.]

12th century

There are a number of carved stones in the church that have been dated to the 12th century and all have been reused in one way or another. Some of the pillar capitals in the nave arcades fall into this category, with the pillar bases and pillars themselves are considered to be newer. A number of carved stones have been reused as building stones in the west wall of the nave,three of which are definitely stones from earlier arches and a fourth that probably is, as well as a Cresset or oil lamp.

I have come across no suggestion of how these stones came to be there. It could be that there was an earlier stone building on the site, possibly to the same plan given the presence of captitals that could be reused. The stones in the west wall are more general and could have come from earlier arches in the chancel, had that been an earlier building in its own right. There has been much rebuilding of sections of the chancel.

The north arcade has one pier with a tall moulded capital and two piers with short moulded capitals, almost like imposts in their position and form. The arches are plain. [crsbi but no specific date given]

DSC_0457.jpg)

The two types of capital in the north arcade

The two central piers of the south arcade have 12th century capitals, having scallops with open mouths without separate abaci [crsbi].

One of the 12th century capitals in the south arcade

On the west wall of the north aisle is a 12th century grotesque carving, originally from a corbel, at eaves level on an external wall. The church leaflet suggests this was reset here in the 12th century, slightly different from the Royal Commission's 13th century date and their suggestion that it is in its original position. The two other stones in the church positioned in the same context are at the east ends of the aisles. These are of later plainly decorated design, (see nave arcades further down this page for pictures).

The 12th or 13th century grotesque carving

See here for discussion and pictures of the arcades.

13th century

The chancel walls are of early 13th-century origin. [Royal Commission]

The chancel, nave and aisles may be of one build of about 1200 although the detailing of the north arcade capitals suggests a slightly earlier date [Royal Commission]. Other authorities consider that these capitals were reused from a building dating to earlier in the 12th century.

The plain round-headed south chancel door might be original 12th or 13th century fabric or a 17th century rebuild [Royal Commission].

The chancel south door now leads to the vestry

Both side walls of the chancel have been much rebuilt; evidence of this is visible of the external face of the north wall and internal face of the south wall [Royal Commission].

Left: The north chancel wall

Right: The south chancel wall showing (right to left) blocked south doorway set in a modified part of the wall, window, vestry door, window

The crooked chancel arch is built of alternating white and brown stone and is thought to be contemporary with the original church building; Butterfield is said to have rebuilt the responds (half pillars on the walls) in 1870 leaving the crooked form of the arch unaltered [Royal Commission]. Pre-restoration paintings and drawings suggest that the responds were altered very little, however, if at all.

The chancel arch

The west doorway appears to be mediaeval [Royal Commission].

The west door - the arch over the door is incomplete, possibly made up of stones reused from earlier in the life of the building

It is interesting to speculate whether any might also be Romanesque carved stones, placed with the plain reverse side facing outwards

The taxation of Pope Nicholas IV, carried out in 1291-2 simply states "Ecclesia Albi Monasterii cum vicaria consolidata: £20". Essentially this says that the church of Whiteparish with consolidated vicarage (vicarage consolidated with the rectory) is taxed at £20. Matcham page 11 adds that among the benefices belonging to the communia of Sarum the church is valued at £13. 6s. 8d.

The wagon roof in the chancel is dated less precisely by the [Royal Commission] to late Mediaeval (1250-1500).

The chancel roof

The four-bay nave arcades are early 13th century except the westernmost pier and respond on the south side, which are 14th century and the east responds, which are Victorian. The greensand arcade columns have round moulded or scalloped capitals and carry pointed arches of two unchamfered orders. Authorities differ on these dates, some suggesting as early as c1200 for the building of the arcades. See here for more details of the north and south aisle arcades and the chancel arch.

The north (left) and south (right) nave arcades viewed from the west

see here for a detailed description and photographs

14th century

In 1324 a licence was granted for the acquisition of the rectory and advowson of Alderstone in Whiteparish by Amesbury Abbey (Benedictine nuns) [Royal Commission and British History under Amesbury Abbey]. This may be the last recorded use of the name Alderstone for the church, but note that it overlaps use of Whiteparish/Whitechurch by at least 46 years.

The octagonal column at the west end of the south aisle, which has a matching half pillar on the west wall

In the mid-14th century the western part of the south aisle was rebuilt and the west front given a new door and window [Royal Commission]. All the openings and the roof in the chancel are Perpendicular (1350-1550) except the plain round-headed south door (original or 17th century rebuild) [Royal Commission]. The two octagonal columns with more complex moulded capitals are as a result of this work [church leaflet and Royal Commission].

15th century

In the 15th or early 16th century the chancel extensively remodelled [Royal Commission].

The east and west responds and west pier of the south arcade date from the 15th century [crsbi]. These are the three responds corresponding to the grotesque face already referred to above and can be seen in the section on nave arcades further down this page.

Late in the 15th century or early 16th century the small Norman chancel east window was replaced with the present one (the glass dates from later, in 1853) [church leaflet]. I've not been able to trace any picture or record of this Norman window so it is almost certainly an assumption that there was one up to this date (quite possibly not unreasonably). A later date of the 17th century is suggested by the Royal Commission - see below.

16th century

I have so far found no changes dated to the 16th century.

17th century

Early in the 17th century the south aisle was rebuilt or recased and new windows inserted with stone window frames [Royal Commission]. These windows no longer exist, the aisle wall later being replaced by Butterfield, so this identification is probably based Buckler's painting below.

The three bells date from 1622: In God is my hope; 1622 again: Give God the glory; and 1631 O give thanks to God. There is more about the bells and photographs further down this page here.

Buckler's 1805 painting showing the 17th century south aisle windows, which were replaced in 1870 with the present ones

The tracery of the east (chancel) window, with its transom and sparse cusping, may date from the early 17th century [Royal Commission]. This date conflicts with the one given in the church leaflet, dating it to the late 15th or early century (see above).

The chancel south door might be a 17th century rebuild (or original early 12th century) [Royal Commission] (see 13th century above - this is an example of where different authorities have suggested 12th and 13th century dates).

The 17th and 18th century woodwork and hatchments recorded in drawings of before 1870 have disappeared [Royal Commission]. See here for these drawings and paintings. However, we do know the families these hatchments belonged to, as George Matcham put a list of them, made in 1838, in his book 'Hundred of Frustfield' in 1844.

List of hatchments in 1838 from Matcham page 119

18th century

The 18th century north aisle was given a similar treatment to that of the south aisle in the 17th century, but this time with wooden window frames [Royal Commission]. As before, this assessment must have been made from the pictures shown further down this page (here) as the aisle was demolished by Butterfield in 1870. In this case as well as drawings there is a photograph taken shortly before work began.

The north side of the church in 1869 before restoration.

19th century

The church clock face dates from 1862, although the iron framed clock in the tower that originally drove it was probably much earlier in date. These early clocks were designed to chime the quarters and hours and often later modified to drive the hands of a clock. Other later improvements would ofen include changes to enhance the accuracy, but as the clock is now in pieces some of this history may be difficult to recover. The clock face having been fitted a few years before the Butterfield restoration, it can be seen in the pre-restoration photograph above, when it would still have been quite new.

In 1870 the nave and aisles were restored by William Butterfield, the aisles rebuilt to a new design, a north porch added and the west belfry replaced but in approximately its original form; the church was almost completely refitted. As a result the exterior of the north and south aisles and porch is 19th century work of flint, chequered with heathstone and Chilmark [Royal Commission]. The work was commissioned by Horatio, 3rd Earl Nelson, and his mother Frances Elizabeth, the final heiress of the Eyre family of Brickworth House and the dowager Countess Nelson of the 1842 Tithe Map. Frances was married to Thomas Bolton, who became 2nd Earl Nelson for a very short period of just a few months before his death. There are more details of the Butterfield restoration below and details of the Eyre and Nelson family [here - add link].

Inside the west end - Butterfield's layout of west door, north door and the staircase to the bell tower

as well as the ceiling panelling under the tower and over where the west gallery had been

Late in the 19th century and probably as part of Butterfield's restoration work the plaster ceiling in the chancel was removed, leaving the beams exposed as they are now [Royal Commission]. The nave roof is also from this restoration, so is a Victorian rebuild. It replaces a partly ceiled late mediaeval one that had moulded feet to its principals as shown in the watercolour below. The woodwork of the 13th century chancel roof remains and a photograph can be seen above, here (to find it, scroll down through the 13th century section after using this link).

The nave roof looking east and the moulded feet in the old roof (from the 1869 watercolour below)

Up to this time the west front had only one central window, and the tracery design was repeated when Butterfield added widows in the west walls of the aisles. The font and pulpit were also designed by Butterfield.

The font and pulpit, designed by Butterfield and part of his 1870 restoration of the church

In August 2022 the font was moved from the southwest corner of the church to a position in the central aisle close to the west door. The photographs below show the pieces laid aside while the new foundation was prepared. See Giles Eyre (4) for a description of the gravestone visible in the floor. The font had already been moved from its original position next to the north door in recent times. (Date to be confirmed - between 1983 and ~2000).

%20and%20Mabel%20his%20wife%20109-DSC_0852.jpg)

The font in pieces during its move in August 2022 and its new foundation being prepared

20th century

1969 an octagonal vestry designed by A. Stocken was added south of the chancel [Royal Commission], and this was dedicated and blessed in February 1970 by the Ven. S B Wingfield Digby. A further extension to the east added an outside toilet in about 2000 [planning permission granted 7.5.1999].

The vestry - left: from the southwest; right: toilet and entrance from the east

Monuments and painting

I have a further section to add on selected graves and monuments and covering the J.F. Rigand painting. This is currently on a separate web page pending later uploading.

Selected features of the church

The chancel

Whether the chancel was built along with the rest of the church in about 1200 as suggested by some experts, or whether it represents an earlier Saxon or Norman church in its own right, it certainly poses some intriguing puzzles in deciphering the stonework. Lets start with the outside of the north wall.

The north wall of the chancel and detail of the arches

and what has been described as a rectangular panel but is more probably a later window or squint.

Here's a tentative attempt at deciphering this wall. Two arches were added to an aisle or vestry this side (north) of the building. When the rightmost was filled in a window opening or squint was left at its centre, which was itself later filled. The leftmost arch is truncated just after the first upper stone, suggesting the section of wall to its left was rebuilt or refaced later. The stone dressings at the left corner of this wall are of similar design to the arches, having dark "heathstone" throughout. By contrast the southeast corner of the chancel has alternate dark and light stones, reminiscent of the chancel arch. Some caution is required with this alternating dark/light motif, as it was imitated in various places by Butterfield in his 1870 restoration (for instance the east and west windows of both aisles and along the length of the east and west walls of the aisles).

A point worth noting is the line of bricks at the foot of the left section of the wall, and again [check] along the east wall. These may help in dating their possible rebuilding and also suggest that they may have been reconstructed together at the same date. It this is right then some of the stones used in the northeast corner might have come from the lost arch in the east wall. [Make some measurements of stones in the remaining arch and in the corner/on the wall itself.] Whether the alternating dark/light stones of the southeast corner were earlier or later than the dark stone on the northeast corner, and whether either might be original will require further work by experts in the field.

Stone patterns: SE corner of chancel alternate colours, NE corner of chancel dark stone

The remaining (rightmost) arch in the north chancel wall is clearly a wide and slender structure, and it would seem entirely possible that the leftmost one collapsed at some stage, leaving no traces in the rebuilt wall other than scattered blocks of the dark stone used in the rebuild. Some of the stones used in the "window" in the right arch are possible candidates for having been part of the left arch, including some of those within the window fill. Some authorities have suggested that these stone arches may simply have been decoration in an otherwise plain wall.

[Cover the east end of the chancel here - photograph needed.]

The outside of the south wall of the chancel offers fewer clues as to its history. It is noticeably poorer in surface flatness and alignment and has had a buttress added at the southeast corner to strengthen it. The wall is entirely [check] rendered, so hiding any alterations or rebuilding that may have taken place.

Inside, the story is reversed, and it is the south wall that offers the more intriguing possibilities.

The south chancel wall showing (right to left) blocked south doorway, modified part of wall, window, vestry door, window and the same from the east

The first photograph above shows the chancel arch in the foreground, recut by Butterfield in 1870, then behind it a section of wall that curiously thins towards the base, both this side and beyond a tall, narrow blocked doorway. The second picture shows this same area from the east.

The chancel arch

The chancel arch is a striking feature in the church, with some very evident and puzzling imperfections. The church leaflet claims that it would seem to have been reshaped from a round headed Norman arch, although this is by no means certain. The misshapen appearance is hard to understand. Did it settle when supporting timber was removed during construction, was it built without a former to act as a pattern or did something go wrong later? Butterfield chose to leave it untouched, which was probably a wise decision. The arch has alternate light and dark stones and on the nave side smaller stones above the arch reflect this pattern, although not precisely at all points. On the chancel side these small stones are all dark ones, reflecting the design of stonework on the outside of the north chancel wall. As mentioned elsewhere, the earliest appearance of this alternating stone pattern is in the southeast corner of the outside of the chancel wall and in this arch, and Butterfield used it in a much more refined and precise way over all the nave windows in the north and south aisles.

The chancel arch - two modern photographs and the pre-restoration drawing of 1869

It is said that the bases and capitals of the responds (the half pillars on the chancel walls forming the vertical part of the arch) were recut by Butterfield, and certainly they are very cleanly cut. Close examination of the pre-restoration drawings of the chancel below [link] suggests that the earlier design was of the same pattern, although Butterfield may have recut them more precisely.

Chancel arch respond capitals: north by pulpit, south by organ

Chancel arch respond bases: north by pulpit, south by organ

On the left (north) side, the first two stones of the arch have been partially reshaped, removing a substantial amount of material and leaving a curious scallop in the edge. Whether this was an aborted start on reshaping at some date, an imperfection present from the start or removal of material to obliterate some defect in the stone is hard to tell.

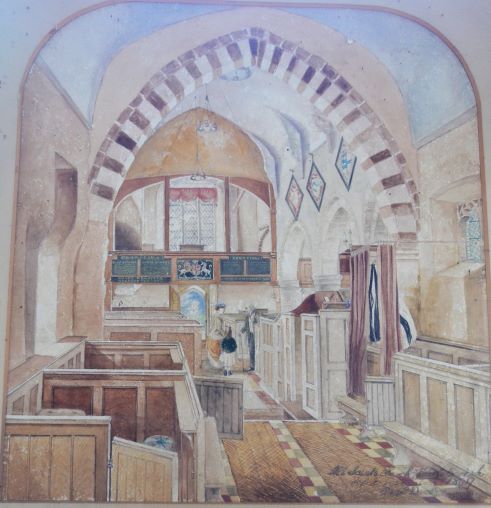

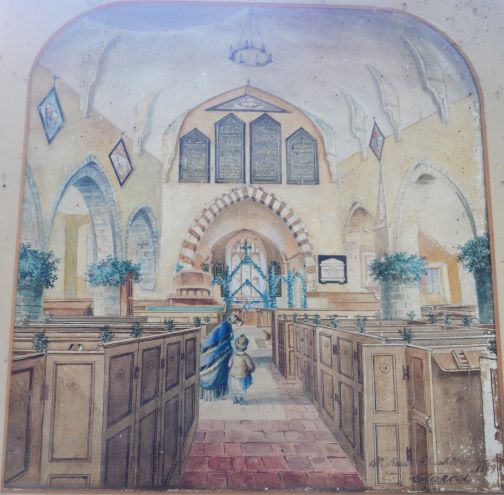

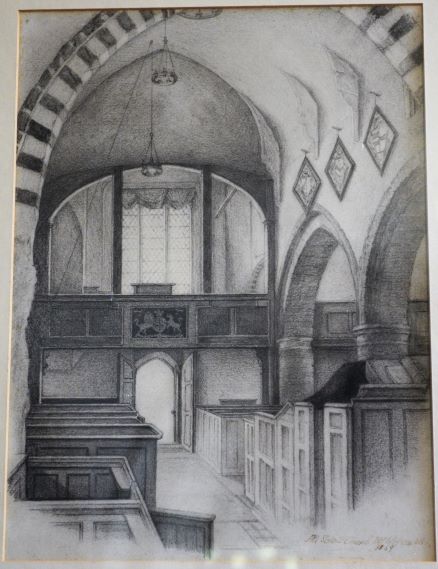

The west gallery

Whiteparish had a west gallery right across the nave and aisles that occupied the western bay of the aisles so that the last arch of the arcades was under it. It is portrayed very clearly in the first of the watercolours below [add link] and in two of the three black and white pictures that follow. These pictures show the gallery extending across the nave and north aisle and I have assumed that it also crossed the south aisle. No access stairs are visible in the pictures and it is very logical that these would have been in the south aisle under the gallery. Somewhere there must also have been stairs or a ladder up into the tower and presumably a removable floor section in the centre of the gallery to match that in the tower and through which the bells would be passed in and out of the tower. The gallery is shown with a panelled wooden front and two uprights in the nave that supported an arched top panel. In the centre of the panels over the centre of the nave was a (royal?) coat of arms [identify this]. A curtain pelmet is shown on or near the west window and the arched top of the west window appears to have been above the ceiling of the time. Above the gallery an ornamental arch, presumably of wood, reached across the ceiling. West galleries went out of fashion around the end of the nineteenth century.

.jpg)

Extracts from the three pictures showing the west gallery

Butterfield took out the gallery, widened both the north and south aisles and presumably built the present open staircase up from the west door chamber to the tower, where three bells still hang.

The bells and clocks in the tower

There are three bells in the tower, hung to allow them to be rung in the conventional manner but in recent years always in the down position with cords attached to the clappers for tolling from by the west door. Salisbury Dioscesan Guild of Ringers describes the installation as 3 bells: 10-0-0 cwt (1,120 lb, 508 kg) in Ab, this weight and pitch presumably being that of the largest (tenor) bell.

The bells are inscribed as follows [Matcham in addenda and corrigenda for p18 line 37 at the foot of page 124]:

- In God is my hope. 1622

- Give God the glory. 1622

- O give thanks to God. 1631

DSC_0554.jpg)

.jpg)

The three bells (left to right: south, centre, north)

For an introduction to how the bells are mounted and used, see this Wikipedia article.

It is many years since the bells were deemed fit to ring from the tower, although I am pretty sure this was still done when I first moved to Whiteparish in 1983. Roger Keeley died in 1987, and by then doubts had been voiced about whether the bell frame and tower were strong enough, and two ringers would toll the three bells before services from ropes alongside the west door. Use of the bells ceased completely when electronic bells were installed about ?2000?, except on special occasions, notably institutions of new clergy. On a topical note, from 23rd March 2020, the three bells were being rung three times each day five minutes before the 9 o'clock morning prayer and 5 o'clock evening prayer while services were initially suspended during the coronavirus pandemic. Sadly this was interrupted shortly afterwards when the order was made to close the church.

Looking down from west window - the three ropes seen here allow the bells to be chimed from next to the west door

The clappers are always struck at the same point on the two opposite sides of each bell as the fixings don't allow rotation of the bells to even the wear and in consequence deep grooves have been worn at these points over the centuries: 1622 to 2019 means they had nearly four hundred years of regular use before they fell silent. Some bellringers take the line that they shouldn't be rung as a result, others consider this normal wear and tear and no reason for the bells to stand silent. It is difficult to avoid speculating on whether it might be possible for the bells to be swung properly in 2022 and 2031 to celebrate the 400th anniversaries of their casting.

.jpg)

The 1862 clock face

Also in the tower is a large iron framed clock, mounted near the south side of the tower. From it a shaft crossed the tower to drive the clock face outside on the north side of the tower. The clock is believed to date from very early in the 18th century and initially had no clock face, merely chiming the hours (and possibly quarters) in much the same way as the famous 1386 one in Salisbury Cathedral. Two clock experts have since suggested a slightly later date of no later than 1750 on the basis that the gears are brass and not iron [e.g. Wessex Clocks Steve on 3.8.2023]. A decision was made to add a "dial plate" at a Vestry meeting on 20th June 1770. This clock face was replaced in 1862 with the present clock face, which was retained in the 1870 restoration and itself restored when the tower was reshingled in about 2000. The clock continued in use until very recently, and I well remember the verger having to climb the ladder and staircase into the tower every week to wind the clock and striking mechanisms. The pendulum is mounted close to the clock and is still in position, with a period of three seconds. The weights driving the clock are extremely heavy, and winding must have been an arduous task; one can be seen standing to the right in the photograph below. After decommissioning, the clock was largely dismantled and the parts left gathering dust as seen in the photograph below. However the steel cables connecting the weights to the winding drums are still in position, as are the pulleys over which they travelled. The striking mechanism driven by the clock is also still in place and in working order.

Parts of the old clock as left abandoned after dismantling

A much more detailed description how the clock worked and photographs of the mechanism can be found here

The old clock was decommissioned and replaced in about 2000 by an electric drive that has proved to be a mixed blessing. The village still [2019] suffers from frequent power cuts and every time there is a cut the clock corrects itself by timing the duration of the power cut then running backwards for the remainder of twelve hours plus half the duration of the power cut. Needless to say this seemingly curious algorithm doesn't always leave the clock showing the correct time, particularly if there is a further power cut before twelve hours is up. By loosening a screw the hands can be rotated from inside the tower, but there is no way of knowing where the hands are except by going outside, which makes for a lot of trial and error and considerable exercise going up and down the staircase to the tower. The bells were replaced at the same time by a set of loudspeakers and a digital recording of bells. This is unconnected with the clock itself so rings the quarters and hours correctly regardless of what time the clock indicates.

To bring the story right up to date, the new clock mechanism failed during the summer of 2021 and by a remarkable coincidence the three loudspeakers also failed at about the same time. New speakers have been purchased and it is hoped to have the recorded bells sounding again before Christmas 2021. Plans are also in hand to have the clock face running again before long. In the event it was 2023 before the clock mechanism was replaced using a generous donation [donor recorded] and shortly afterwards Ivor Ellis fitted and commissioned new loudspeakers. [Add the dates from my diary entries.]

.jpg)

In the tower - the old clock frame and ladder to reach the bells; the new clock mechanism; one of the loudspeakers for the electronic bells

The 1870 Butterfield restoration

In 1870 the Nelson family commissioned William Butterfield to carry out an extensive restoration of the church. Close examination of the structure, together with "before and after" photographs and paintings of the church, shows that he completely demolished and widened both the north and south aisles, rebuilt the tower and probably replaced the nave roof. His characteristic patterned stonework on the outside wall made up of dark and light stone and panels of knapped flint replaced all the earlier structure in those parts, including the east and west ends of both aisles. The join to the older fabric of the building can be seen clearly on the outside of the east and west walls of the nave. Butterfield was a Gothic revival architect associated with the Oxford Movement, and this suited the high church leanings of the dowager Countess Nelson and her son Horatio the 3rd Earl Nelson.

The church before and after restoration by Butterfield, in 1869 and 1870 respectively

The Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 6th May 1868, Image (c) The British Library Board, all rights reserved

Western Gazette Friday 6th May 1870, Image (c) The British Library Board, all rights reserved

The Royal Commission book places the context very neatly: "The role of the Radnor family as sponsors of matters ecclesiastical in the south-east part of [Wiltshire] was partly taken over by the newly established great family, the Nelsons. Although Standlynch was acquired on their behalf by parliamentary trustees in 1815, the dynastic misfortunes of the first earl losing his son and the second earl, the Rev. Thomas Bolton, dying in 1835 only a few months after succeeding to the title, meant that it remained for the third earl [Horatio] to confirm the family's prominence in the area. This he achieved partly because of his very long life (he lived until 1913) and his involvement in public, especially church, affairs, but chiefly through the influence of his mother, Frances Elizabeth Eyre, who was sole heiress to the great estates in [Whiteparish] belonging to her branch of the [Eyre family], owners of Brickworth House and the Nelsons. Her marriage to the second earl gave the Nelsons the local base and connections they lacked and the Eyres the title they sought."

In 1813 the Standlynch estate had been acquired by Act of Parliament as a gift to Admiral Lord Nelson's brother (the 1st Earl Nelson) and his heirs to commemorate the Battle of Trafalgar victory of 1805 and the estate renamed Trafalgar Park. Land around the park was purchased at the same time to add to the estate, including 504 acres recorded in 1842, joining up the Standlynch and Brickworth estates as a single unit.

Horatio Bolton Nelson inherited the title of 3rd Earl Nelson on his father's death in November 1835, but as his mother survived until 1878, Horatio had a long wait to inherit the Eyre family estates and fortunes. Whiteparish All Saints church was restored by William Butterfield in 1870, so with her great wealth it is natural that his mother influenced his choice of architect and contributed to the project. Horatio and his mother were both enthusiastic builders and restorers of churches and Horatio had already employed Thomas Henry Wyatt as the architect for a new church at Charlton All Saints. The congregation at Charlton had no church and had for centuries worshipped at Standlynch chapel so by building the new church the family was able to make it their private chapel. It had been Wyatt too who had designed the spectacular new Italianate church at Wilton (1841-1844) for the Countess of Pembroke and her younger son Baron Sidney Herbert of Lea. Butterfield was to go on to restore the chapel at Trafalgar House (Standlynch).

Butterfield's characteristic combination of materials in All Saints church Whiteparish

It is perhaps serendipitous that the two colours of stone and extensive flintwork of the pre-restoration church allowed Butterfield to accomplish his penchant for patterns using these materials and stay away from bricks - just envisage Whiteparish church in the style of Butterfield's other masterpiece of 1870, Keble College in Oxford. As a Keble graduate I must of course claim to be unbiased in my preferences.

Keble College, University of Oxford [replace with one of my own photographs]

Photograph by David Iliff. License: CC BY 2.5

For the windows in the west wall of the north and south aisles Butterfield copied the style of the pre-existing west window, but for the north and south walls he substituted his own design.

DSC_0542 resized.jpg)

DSC_0541.jpg)

The window designs in the aisles - here the eastmost and westmost windows from the north aisle

Inside the building Butterfield took up the theme suggested by the southeast corner of the chancel and the chancel arch in the design of the stonework above all ten new windows.

I'd love to find a reference to what the people of the village thought about the project at the time and how they coped with with what must have been a considerable upheaval to the life of the church at the time. I feel sure that economy of labour would have been an important constraint. Butterfield widened the aisles, which means that he could have built the new north and south aisle walls without first demolishing the old ones, and indeed this may have been the reason for widening the building. The east and west ends of the aisles, however, did have to be removed completely to be tied into the new work. Given the size of the original buttresses, I would speculate it might have been possible to leave the roof in situ over the aisles until the new aisle walls were complete and ready for the new roof line. Careful examination of the Buckler watercolour of the south and west faces and the photograph and drawing of the north side suggest that the roof line on the south side descended fairly evenly behind a parapet and on the north side a change of slope to to a very shallow angle took the roof across the aisle. Butterfield's modest change of roof angle across the aisles could quite possibly have followed the earlier angle of the south aisle roof and thus dictated what to do on the north side. It appears from the timbers inside that the tower was probably completely rebuilt with new materials, and analysis is ongoing to provide a detailed structural description here.

The north and south aisle arcades and the chancel arch

Four of the columns with 12th century capitals (the fifth is below to the left)

The south arcade viewed from the west (left) and east (right)

The pictures that follow show details of the top and base of each respond and pillar in the south arcade, from the east on the left to the west on the right, matching the order in the two photographs above. Note the block of dark stone under the eastern respond next to the organ (top left picture), a block which corresponds with the grotesque face on the west respond of the north arcade (see picture below). There's a blank picture in place of the base of the east respond as there is no base.

DSC_0445.jpg)

DSC_0449.jpg)

Respond: 15th century, Capitals: 12th century , 12th century , 15th century , Respond: 15th century

Piers: 13th century, 13th century, 15th century, Respond pier: 15th century

DSC_0446.jpg)

DSC_0450.jpg)

The next set of pictures shows the north arcade. I've put these in the right order to correspond to the general views, so this time they go from west on the left to east on the right.

The north arcade from the east (left) and west (right)

Next come pictures of the top and bottom of the north responds and each of the north arcade pillars between them, this time with west on the left, east on the right to match the general views above. It is particularly clear here how the west respond near the north porch and door of the nave has been carved into a grotesque face, whereas the east respond next to the pulpit and its partner opposite on the west arcade next to the organ have been left as simply decorated stones.

DSC_0462.jpg)

DSC_0457.jpg)

DSC_0458.jpg)

Capitals:

DSC_0461.jpg)

DSC_0456.jpg)

The north and south aisles

The north aisle (left) and south aisle (right) looking eastwards

The charity boards in the porch

There are two charity boards in the church porch, one showing gifts given in 1704 to the Boys School and in 1745 and 1750 to the Girls School and the other donations made in 1832. Both were originally mounted on or painted directly onto the west gallery panelling, as clearly shown in the extract from the 1869 watercolours of the church below. The boards were preserved when the west gallery was demolished by Butterfield in 1870 and the painting of 1869 is detailed enough even to see the way the tops of the frames were modified after removal from the gallery by adding a top to the frame and reproducing the lettering thus covered up. These boards are so faithfully rendered in the painting that I assume the dark background shown is artistic licence. Of course, if the charity donations were signwritten directly onto the gallery panels, then these boards are a relic of the gallery itself.

Left: The schools charity board showing gifts of 1704, 1745 and 1750 towards schools (on the west side of the church porch)

Right: The charity board of 1832 (on the east side of the church porch)

An extract from the 1869 watercolour showing the front of the west gallery at the back of the church. The charity boards from the front of the gallery are now displayed in the roof of the north porch. Frames were added after removal from the gallery, and the original headings of Charities and Donations are now covered by those frames, both now headed Charities

For the present All Saints church school and its predecessors over the years, see schools.

Rectors and Vicars of Whiteparish Church

Rectors and Vicars of Whiteparish Church

Vicars and Rectors of the church are listed on a separate page here.

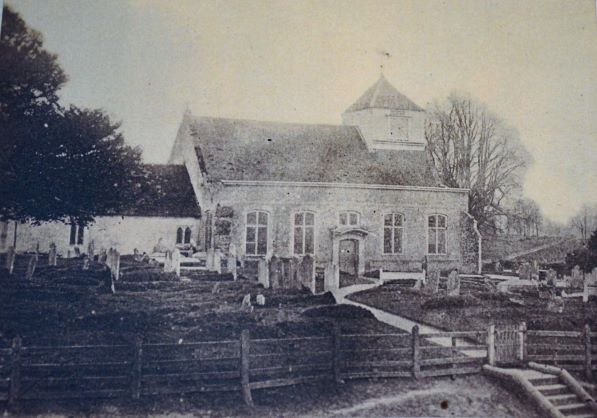

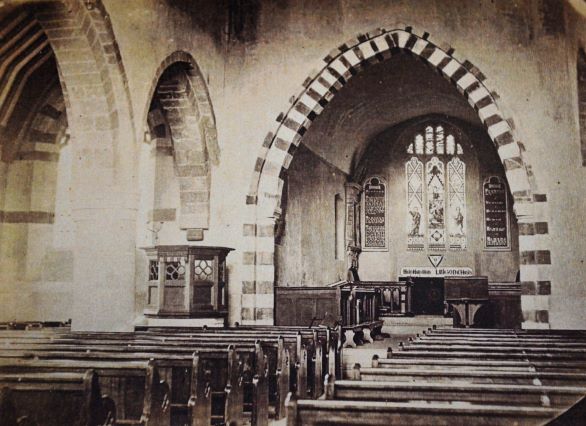

The outside of the church before and after the 1870 restoration

The church was "improved" in two stages: the interior in 1853 and then a major reconstruction in 1870. We are fortunate to have a comprehensive record of how the building looked, at least before the 1870 restoration, in the form of paintings, drawings and photographs. A good selection is displayed at the back of the church. Here are a few, both from that collection and elsewhere, together with a few up-to-date photographs for comparison.

It is appropriate to start this section by repeating the earliest known image of the church, painted by John Buckler in 1805 and showing the old church from the south side. Buckler was well practised in his art, and by the end of his life had produced some 13,000 drawings of buildings. Among these were a locally important commission he received from Richard Colt Hoare of Stourhead shortly after 1800 to produce ten volumes of drawings of churches and other historic buildings in Wiltshire, and among which are this picture and that of the St Barbe Manor house that stood next to it from 1562 to 1812.

The church from the southwest in 1805, watercolour by Buckler

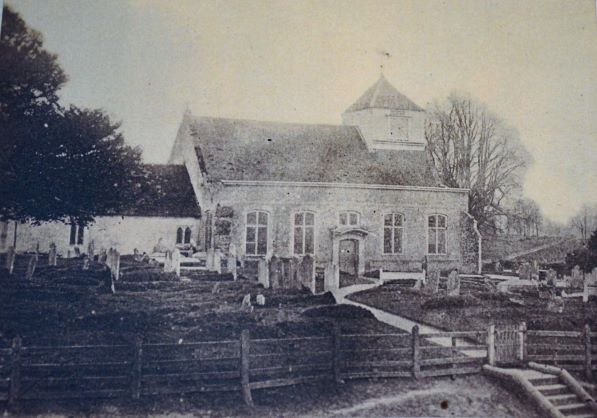

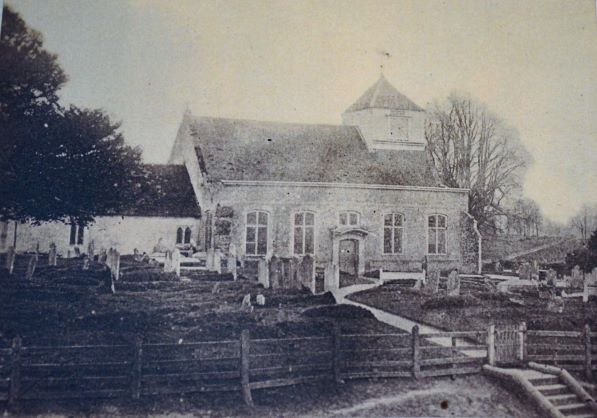

These next two photographs appear to have been taken as an intentional record of the changes to the building, one just before the 1870 restoration by William Butterfield and the other just after. The pictures were presumably taken upstairs in the White Hart. Much of this view is now blocked by trees.

The church from the north, photograph taken before the 1870 Butterfield restoration. This and the photo above are clearly a deliberate record of the "before and after", taken from the same viewpoint.

The church from the north, photograph taken after the 1870 Butterfield restoration. Compare this with the picture above taken from the same viewpoint a year or two earlier.

These pictures show several points of interest, including the steps leading up from the road opposite the White Hart and the fence and gate, which has more recently been been replaced by a wall. A map of roughly the same date is shown below for comparison. The extensive grave mounds shown are in the area of the churchyard on the left side of the path are in the area now full of modern burials. Behind and to the right of the church can be seen the footpath that starts across the road from the surgery. It is worth noting that the churchyard extension down to the Surgery car park was added between 1910 and 1925, so the part of the churchyard that runs down to the St Luke gate wasn't there at the time. At this date, in place of the earlier St Barbe Manor House, there was a smithy out of sight behind the church associated with the Whiteparish brickworths, which were still in use in 1870.

The area included in the views above from that 1870 OS map [(c) Old-maps.co.uk - zoom out after opening this link to see the map]

A black and white drawing of the north side of the church before the 1870 restoration

A view of the vicarage and church taken from Parsonage Meadow [post 1870 - date?]

The church porch, vicarage and thatched lych gate (later than the Butterfield restoration of 1870)

Inside the church before and after the 1870 restoration

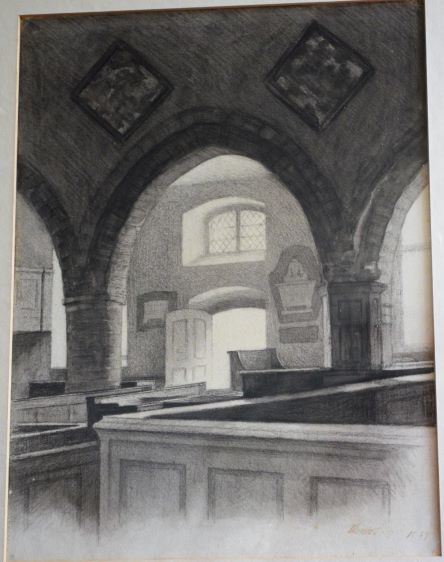

A fine pair of watercolour views was painted in 1869 on the eve of the 1870 Butterfield restoration, one looking west and one looking east. Some of the things to look for in these pictures include the west gallery occupying the last bay of the church at the west end, the box pews throughout the church and also in the chancel, the plastered ceilings and of course the lack of an organ. These paintings are clearly labelled 1869 and Butterfield's restoration is recorded as 1870, so it is probable that these were intended as a record of how the church looked on the eve of these works. There are also three black and white pictures, the composition and rendering of which make it certain that they were by the same artist. Some are very precise copies of the watercolours (or vice versa) while others differ very slightly in certain details - for instance note the different number of dark stones on the left side of the chancel arch between the first watercolour and the first black and white drawing below.

Interior of church looking west and east, painted in 1869, the year before Butterfield's 1870 restoration

A black and white drawing of the chancel from the centre of the nave, with box pews

dated 1869 and almost certainly by the same artist

The first of the black and white pair below is a faithful copy of the watercolour from a slightly advanced viewpoint, although again with slight alterations in detail (again a different number of stones in the chancel arch, for instance). The one on the right shows the view through the second arch of the north aisle arcade (from the east) through the north door. This door was centrally placed in the north aisle before the restoration (see the external pictures above). Butterfield moved it to its present position further west, in the northwest corner of the church. Another feature of these paintings and drawings is the clear depiction of the west gallery, which occupied the last (westerly) bay of the aisle arcades. Butterfield was responsible for its removal. West galleries were going out of fashion at that time and the sections of the structure in the north and south aisles would have needed rebuilding or modifying to accommodate Butterfield's wider aisles. There is more about this gallery above [add link].

Two black and white drawings of the chancel from the centre of the nave, with box pews. This is from 1869, before the restoration,

and by the same artist as the three pictures above

The church interior looking east into the chancel. The pews in the nave are the ones we have today, but the box pews in the chancel remain. Taken after Butterfield's restoration of 1870. This view shows the 10 Commandments boards still on the east chancel wall, so they must have been moved to their present position on the west chancel wall at a later date.

[Consider the window opening on the north wall by the altar which is not visible in the wall outside. Is it still there now?

The south aisle (later than the Butterfield restoration of 1870)

Two views of the interior of the church taken in October 2019, looking east

1. Looking down into the church from the very top of the open part of the tower staircase

2. The decorated woodwork through which the photo was taken

3. The staircase from near the west door (the final section is enclosed at top right)

The "new" organ installed during David Tyrell's time as organist, 1985-[look up] [add link to new David Tyrell page]. Installed in 1996 to replace the previous organ and formerly in Chudleigh United Reformed Church

This picture also shows the chairs that replaced the choir and south aisle pews in about ?2005?. The pew fronts were retained and are now mounted on castors to make it easy to move them.

The Roger Keeley altar and a detail of the bells on the front of it

Memorials

This section collects just a few of the memorials around the church and churchyard for people with particular associations and who are in many cases covered elsewhere in this website. There are too many memorials to catalogue them all systematically, but further memorials will be added here with links to pages with details of the people concerned.

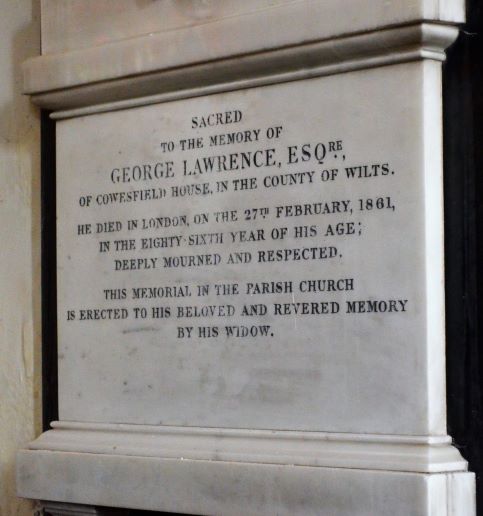

The memorial to George Lawrence of Cowesfield House on the outer wall at the east end of the south aisle. This is the George Lawrence of the 1842 Tithe Map - see George Lawrence Esquire and Cowesfield House

The east window in the chancel, a memorial to Robert Bristow of Broxmore Park, died in 1853. This is the Robert Bristow of the 1842 Tithe Map

Kathleen Hayes memorial plaque on the organ. See Mrs Hayes for more detail

The memorial plaque to Ken Witchell on the bookcases near the north door of the church. I sang tenor alongside him in the choir from 1983 until he retired from singing a few years before his death.

The memorial plaque to Hedley Hammond and his wife Daphne on the north gate to the churchyard opposite his butcher's shop and house Southdown. Hedley's time as churchwarden included the thirty years Roger Keeley was vicar and they now lie side by side in the churchyard near the northeast corner of the chancel

The Graveyard

This section is currently undergoing revision, September 2022, and is incomplete

Also see Churchyard extensions further research and references

With thanks to Dr Rosalind Johnson, author and contributing editor in the Victoria County History team, for kindly providing references and details included in this section. See the (private) link above for contact details.

The graveyard was due to be extended by one rood (a quarter of an acre) and consecreted at the service reopening the church on 24th April 1870 after the Butterfield restoration was completed (see above), but the donor of the land, Mrs Durie, of Broxmore House, was severely ill and not at home. A faculty was later applied for, stating: "Churchyard insufficient for 'purposes of sepulture'. A plot of land of one rood or thereabouts, on south side and immediately adjoining churchyard, by deed of 21 June 1870 has been freely conveyed by Charles Durie of Broxmore Park, and Sophia his wife. The said plot has been thrown into the old churchyard and is substantially fenced, and in all respects fit and ready for consecration." [Research: Did Mrs Durie die and Charles and Sophia inherit the land? Check dates on gravestones in this area and consider the lay of the land]

The Ordnance Survey map of 1876 presumably includes this extension within the churchyard shown, and if this is the case then the land involved is approximately represented by the orange outline on the Google view below. The south edge of this area is the boundary shown on the 1876 and 1900 maps [needs to be positioned more accurately by tracing from the maps]. [Research ongoing.]

.jpg)

Orange speculated 1870 extension and south of that the 1902 extension (Google, recorded as 1st January 2005 but clearly taken in summer, so presumably 2004)

This extension to the churchyard clearly only sufficed for about 30 years' burials. The vicar reported to the vestry meeting held on 3 April 1899 that an extension to the churchyard was urgently required, there being space for less than 20 further burials [vestry book WSA, 830/16]. Further vestry minutes refer to this and a portion of land adjoining the churchyard was purchased from Miss Bristow and Mr Bull and consecrated in 1902 [WSA, 830/16, mins. 17 Oct. 1900, 8 Apr. 1901; Salisbury Times, 17 Jan. 1902, 8]. By chance the 1876 map postdates the first extension and the 1900 map predates the second, showing the same churchyard boundary.

.jpg)

1876, 1900, 1924

Churchyard extensions feature regularly in Parish Council meetings to the present day (2022). The need for an extension was discussed when the church thought it was running out of space a few years ago. The need was avoided then, but very recently the topic arose once more, leading to the purchase of a piece of land on Young's Farm in 2021. Once again the church has since ascertained that more burials can be accommodated in the churchyard. The possiblity of using this piece of land for allotments until needed for burials was considered but decided against at the end of 2022.

The Churchyard Wall

See Churchyard Wall for further information and ongoing research.

In the earliest photographs taken of the church, including those taken immediately before and immediately after the 1870 Butterfield restoration, the churchyard has a simple fence around it. The wall that now surrounds the churchyard was just a short section from immediately south of the Common Road gate that stretched as far as what is now the surgery car park entrance.

The 1870 photograph below shows that this section of wall appeared exactly as it is now, with a rapid fall of height from the gate itself - see photograph 05 below. The white section left of this is probably a gate to the same style as the one in the northwest corner of the churchyard shown below. Beyond the wall and along the length of the church in this photograph, the old churchyard boundary at the time can be seen as a line of vegetation that runs from the left end of the wall to the right across the photograph. This boundary forms the foreground of Buckler's watercolour of the St Barbe Manor House painted in 1805. My working assumption is that this section of wall had been built along the road frontage of the garden of that house. The house was demolished in 1812.

The wall along Common Road from the gate (white) southwards, part of photo 05 here

The three churchyard gates at the time appear from the photos to have been all of the same design of white painted metalwork. The next picture is the clearest, and shows the one on the corner of Common Road opposite the shop and post office of 2023.

The fence in the northwest corner of the churchyard with the white gate, part of photo 13 here. This is the gate on the corner opposite the village shop

The third gate at the time was the one opposite Southdown, visible on the right of this third picture.

The fence and north gate of the churchyard with the white gate, part of photo 11 here. This is the gate opposite Southdown

My working hypothesis is that the wall may have been associated with the St Barbe Manor House that stood on the next plot. The 1876 OS map shows the line of the wall alongside the present layby on Common Road just as it is now, meaning that the whole wall south of the Common Road gate may be original, as far as the pillar and splay at the entrance to the Memorial Ground and Surgery car park, which is probably more modern and is matched on the south side by a similar structure.

These photographs are small areas selected from pictures available elsewhere on this website - apologies for their poor quality.

The line of the wall on the 1876 map, showing the layby as it is now (2022)

.jpg)

The wall at the entrance to the Memorial Ground car park 2022

.jpg)

The wall at the Bunker's Hill entrance to the Memorial Ground 2022

Photographs ready for use

For more photographs of the church, particularly inside the tower and looking down from the tower staircase, see AllSaintsChurch more photographs.htm.

References

References that have been quoted widely on this page are listed here to provide easy access to the source material. If you have private access to the full website then the appropriate extracts of the text and photographs from these sources can be found on the Church Sources page; for copyright reasons this page cannot be made available on the web.

- The listed building status for the church

- Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture [link updated 25.3 2021 to match new site organisation]

- Churches of South-East Wiltshire, Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England, HMSO 1987, ISBN 0 11 7009954 (pages 14, 21, 37-38, 57-58, 71, 74, 205-6), all transcribed on the Church sources page. The article on Whiteparish Church is on pages 205-206: Page 205, Page 206

- Church visitor leaflets, available at the back of the church. I have three of these from different dates between 1983 and 2000.

- Wiltshire County Council Community History

- Matcham p11, Hundred of Frustfield, written by George Matcham for Sir Richard Colt Hoare of Stourhead, 1844

- Wikipedia article on Whiteparish

Acknowledgements

I would especially like to thank Peter Claydon for the opportunity to take photographs of the bells and clocks and of the the inside of the church from above. Thanks too to the Rev. Jane Dunlop, for arranging this visit and suggesting the overhead views.

Thanks too to Dr Rosalind Johnson, author and contributing editor to the Victoria County History of Wiltshire, for information about the churchyard extensions.